SQL implementation of Evita

The document contains the original research paper for the implementation of the evitaDB prototype that uses PostgreSQL under the hood. The implementation tries to translate evitaQL into a SQL query and store all necessary data in the PostgreSQL indexes. The paper describes the positives and negatives associated with this approach and, together with the worst performance results among all alternatives, led to not choosing the PostgreSQL prototype as the path for the final implementation.

Terms used in this document

- DB

- Database

- Index table

- Table used and optimized only for searching data (not retrieval)

- Inner entity dataset

- Collections of items that reside only inside an entity (attributes, prices, references, etc)

- CTE

- Common table expression

- MV

- Materialized View

- MPTT

- Modified preorder tree traversal

- PMTPP

- Pre-allocated modified preorder tree traversal

- ACID

- Set of properties of database transactions

- ID

- Generic unique integer identifier

- UID

- Internal unique string identifier used to represent entity collections

- API

- Application programming interface

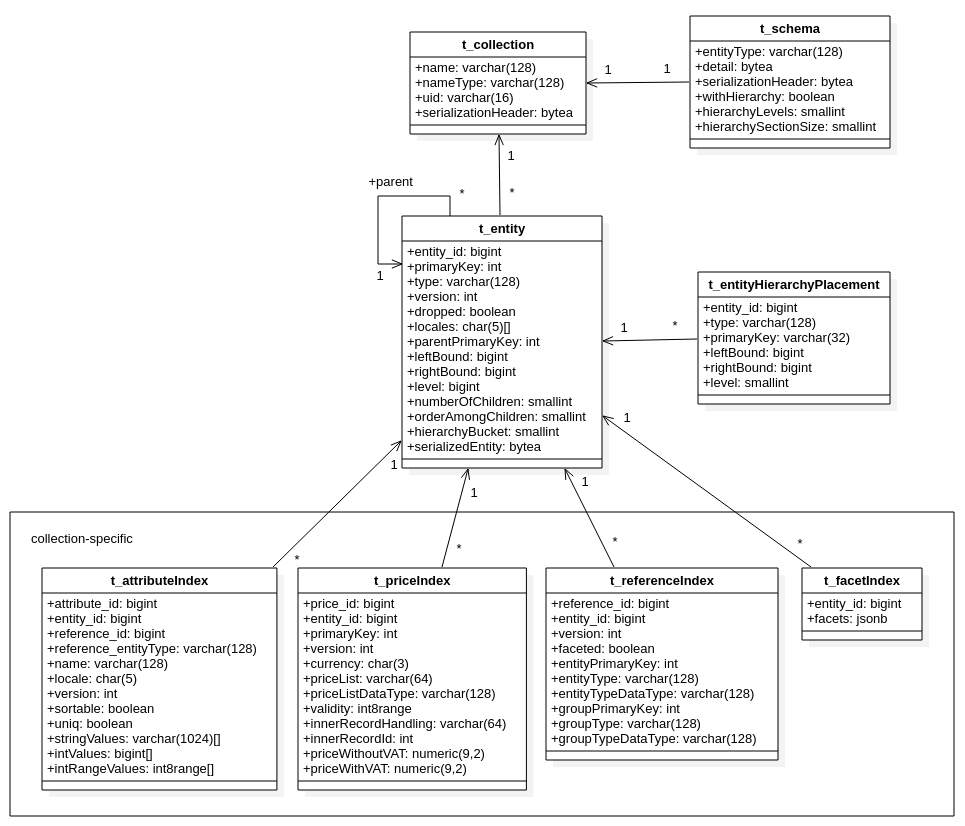

Evita SQL DB structure

Data model

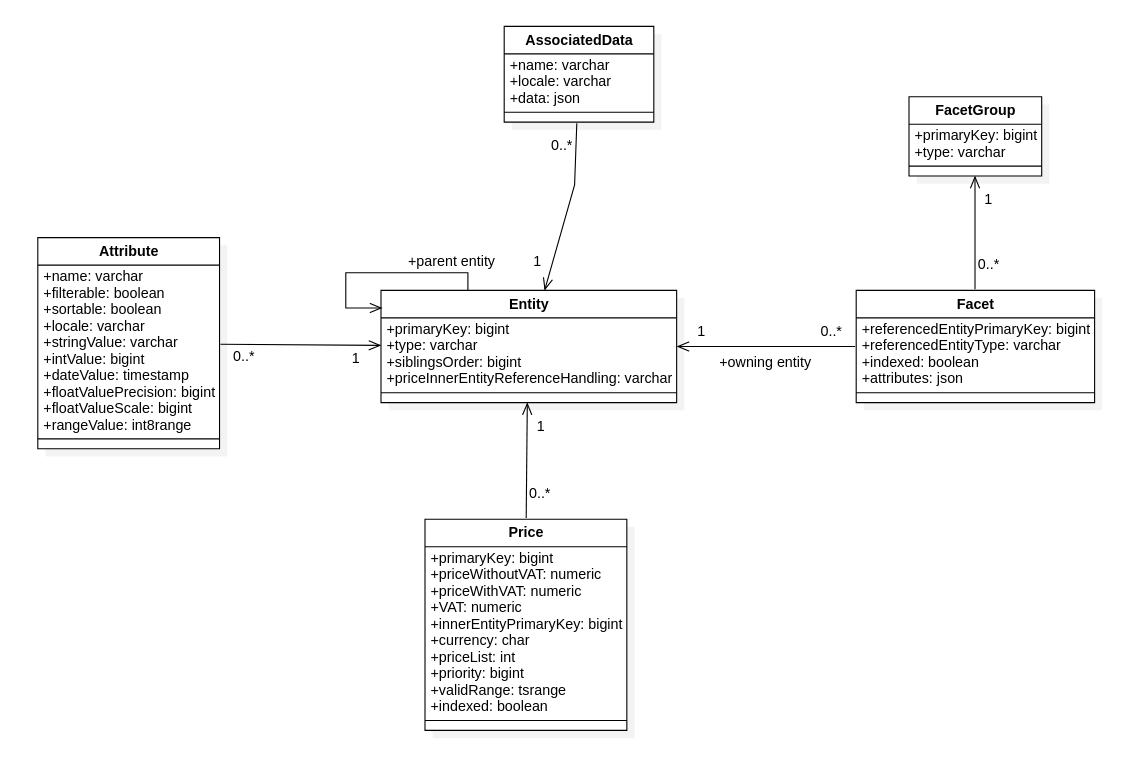

Original model

Original model Updated model

Updated modelAs the figure above shows, there are several essential changes, mainly thanks to a better understanding of the API. For the sake of optimization, other changes were also made. Our original model presented considerable difficulties with the conversion of entities between the Java memory model and the relational model. Furthermore, it did not properly reflect the universality of data types.

The fact that may not be apparent from the schema is that there exists, and we have to work with, two types of entity identifiers. There are internal IDs that are directly related to our implementation of Evita and are not exposed through API and then there are Evita primary keys that are either generated by Evita API or are passed from outside. The reason for using our own internal IDs is that those IDs are globally unique across all collections, unlike the Evita primary keys which are unique only inside a single collection. Therefore, there is no need to specify both the primary key and entity type inside the referenced table to correctly construct foreign keys which simplifies querying and updating. We use PostgreSQL’s sequences for generating and managing those internal IDs.

Overall, the new model enabled us to implement all API requirements for searching and data management and, in our opinion, it has satisfactory performance.

Transactions and the ACID implementation

As a well-established DB, PostgreSQL supports transactions along with the ACID principles. At present, we do not use transactions since their implementation was beyond the scope of our research project. Only the final winning solution will proceed with a further advanced implementation.

However, the actual implementation of transactions would probably mean introducing locks on the whole entities because every time there is an update to an entity, the binary serialized snapshot of that entity has to be also updated. That could lead to performance problems when there would be a lot of small updates to a single entity. Those updates would not even have to be the same data. Each update might modify a completely different part of the entity, yet at the same time, each update would block the entire entity due to the need for a new version of the serialized snapshot of that entity. Fortunately, the PostgreSQL and JDBC drivers have excellent support for programmatic transaction management,which could be used to implement Evita’s transaction API without much difficulty, although this would not solve the problem with the extensive locks.

Some excessive locking could be prevented if we split the entity snapshot into multiple parts, but that would involve more experimenting and testing as it would influence the whole entity storing and fetching processes. It may even affect reading or writing performance because there would be additional overhead with splitting and joining those parts back together as we did with the original model. This may have either a bad impact or a positive impact on performance. However, again, it would involve more experimentation to find the definite impact.

Data insertion and retrieval

As it has been mentioned above, we need to convert our data between the Java memory model and the relational DB model, which was a considerable bottleneck at the beginning of our implementation. Fortunately, we managed to significantly optimize the conversion. Therefore, it does not present the bottleneck anymore.

The main bottleneck was due to the complexity of entity breakdown to several tables. This approach was initially used as it is widely used when storing objects in relational DBs. However, in our case, each entity holds large quantities of data in one-to-many collections (such as attributes, prices, etc.). Therefore, this approach was not ideal.

To better demonstrate the problem, some statistics concerning the Senesi dataset are presented below. Please note that all data were from the 31.5.2022 version of the Senesi dataset.

| Collection | Count |

|---|---|

| Entity | 117,475 |

| Prices of entities | 3,361,040 |

| Attributes of entities | 3,848,705 |

| Associated data of entities | 698,095 |

| References of entities | 967,553 |

In addition, table below shows the average entity from the Senesi dataset.

| Entity inner dataset | Count |

|---|---|

| Price | 28.61 |

| Attribute | 32.76 |

| Associated data | 5.94 |

| Reference | 8.24 |

The average counts of inner datasets may not seem tremendous, but when we need to store or fetch several entities at once, those counts become quite large for SQL DB.

On top of the data size bottleneck, the API uses generics for entity type values, attribute values, or reference values. Therefore, there was a need to convert all of those values to some general-purpose data type (usually a string form) and remember which data type it was originally in order to reconstruct the original value with the correct data type.

We also encountered problems with multithreaded entity writing because we did not implement any transactions, as this was outside of the exploration phase goals. Our solution was to introduce simple thread locks for the entity writing functionality. To support writing from multiple threads in parallel, we would have had to properly implement the SQL transactions first so that PostgreSQL could deal with the data update concurrency. Unfortunately, this would have been difficult and time-demanding to implement and we simply did not have enough resources for their implementation.

Utilization of the Kryo library and optimizations

This reduced overhead for the insertion and thus improved the insertion performance from around 240 minutes (4 hours) to approximately 85 minutes (1.25 hours), tested on the Senesi dataset on the same local machine.

The new approach consisted of breaking the Java objects representing an entity to metadata and individual items of inner datasets. Those items were then serialized using the Kryo library to byte arrays and encoded using Base64. JSON trees were constructed from those encoded strings, storing some basic categorization metadata about those items. For example, attributes were categorized by locales which served as a way to fetch only partial entities by the end-user’s request without the need for storing those items in traditional tables. This also simplified the whole process of fetching data as those JSON trees were stored in the entities table and no joins to the referenced tables were needed anymore. Even though there was significant overhead with connecting all of those pieces together when reconstructing entities, it was still a far better solution than the initial one and provided reasonable results.

Furthermore, we realized that it took about the same amount of time (in some cases even less time) to fetch a full entity using a single byte array as to fetch an entity with only client-desired parts using the complex partial entity fetch. This is mainly caused due to the difference between these two approaches. To get a partial entity, first the JSON structures had to be filtered by the end-user requirements to find targeted items (attributes, prices, etc). These Base64-encoded items had to be decoded and deserialized using the Kryo library and finally, the actual entity had to be reconstructed. For comparison, to get a full entity, a single byte array of a serialized entity with all the data has to be fetched and then simply deserialized with the Kryo library to the original object. Therefore, there is no overhead with the JSON parsing, Base64 decoding, and one-by-one reconstruction. This new approach gave us about a 20-30 % performance gain and a much simpler codebase. It is obvious that if entity contents grow big enough, we get to the point where most of the fetched data would be thrown away because the query does not need them. Thus, the performance would start to decline compared to the more precise fetch of just requested entity parts. However, this tipping point was not discovered when testing with our datasets.

We are aware that there is some additional overhead when using Kryo as Kryo needs to store the metadata about serialized objects somewhere. In the end, even with this overhead, Kryo proved to be a much better solution than the traditional ORM approach. Unfortunately, the conversion of generic values is still present as it cannot be fully replaced. However, thanks to the shift to the index tables and the Kryo serialization, we managed to reduce the places where original data types are required.

In the case of the entity updates, there exist other problems. At first, we tried to update modified items of each entity individually as there is no batch update functionality in PostgreSQL. This approach turned out to be working quite well until we tried it out on the Senesi dataset where we once again encountered problems with large entities, same as the ones mentioned before. Therefore, we tried out another commonly used way of updating objects to relational DB, which consisted of deleting all data of the existing entity from DB and afterwards inserting new data. This enabled us to use the insert buffers even for updating, which led to decent results on the Senesi dataset. The final tested approach consisted of first fetching information about what items and in what versions had been already stored in DB and subsequently comparing this information with the items of the updating entity. Each item was then inserted (using the insert buffers), updated or deleted only when there was a new version or the item was missing. This final approach proved itself to be the most performant solution as it combines the insert buffers and ignoring of unchanged items.

Furthermore, Kryo is also used to store the entity schemas. They are only stored and retrieved, which again allows the use of this simple solution, allowing fast operation with minimal to no drawbacks and no need to model complex table structure.

Finally, to better illustrate the size of the entities Kryo handles in our implementation, we provide data on the size of the Senesi entities. Please note that all data were from the 31.5.2022 version of the Senesi dataset.

| Single serialized Senesi entity | Size (bytes) |

|---|---|

| average | 1,791 |

| min | 341 |

| max | 34,774 |

Catalog isolation

Warming up state - bulk insertion

Even with the previously mentioned optimizations, inserting large amounts of data was painfully slow, as it has been mentioned above with the Senesi dataset. Therefore we focused on properly implementing the Warming up state. This initial insertion-only state allowed us to fully focus on the insertion regardless of the data retrieval.

We improved upon our insert buffers strategy, originally made only for the insertion of the data of a single entity, to be shared between multiple entities. The improved buffers strategy in conjunction with the insert batching led to a rather significant speed improvement for saving entities, all without affecting normal Evita functioning thanks to the “warming up” state. To provide a specific example, while testing the Senesi dataset included in the integration testing suite in a local environment, this change led to a time improvement for full insertion from 85 minutes to 15 minutes.

Another important optimization in the “warming up” state is related to the data indexing. At the beginning, there were only a few indexes, therefore we updated the indexes with every inserted entity. At that time, it was a sufficient solution. Unfortunately, later with a more complex structure and more indexes, we had to rethink our approach as the time of the initial bulk insertion of the Senesi dataset nearly tripled. Initially, we created indexes at the creation of the catalog and its collections, which led to continuous index updating during the “warming up” state. However, we did not need the indexes since the reads do not occur in the warming-up phase. After realizing this, we decided to create just the table structure at the start and create the DB indexes for those tables when the “warming up” state is terminated and the DB switches to a transactional state (this can only happen once for a catalog, there is no going back to “warming up” state after such a switch). This means that data are only indexed once, vastly increasing the “warming up” state indexing performance (tested in a local environment, this optimalization led to a decrease in time of indexation from several hours to approximately 40 minutes on the Senesi dataset).

Interesting side-note

We encountered an interesting problem with integration testing. For a long time, we tried to diagnose why the performance test was not terminating, even if the actual testing finished. We did find out that the tests did finish, even successfully, it just took unreasonably long. The main culprit was the DB, specifically how we reset it for the independent testing without the need to create a new PostgreSQL instance. We found out that the deletion of about 100 thousand entities using the DELETE clause as shown below

Implementation of the query algorithms

Now that we discussed the platform for our implementation, it is necessary to explain the querying implementation itself. This section includes not only the final Evita implementation but also the gradual steps that led to it. The main reason for this approach is to show the creation process, with the hope of providing a context for the final implementation.

Query processing

As it has been stated in the general Evita documentation, Evita has to be able to accept a vast variety of complex queries, which are specified by the user of Evita (developer of the e-commerce system). That led to the creation of the Evita query language which we have to support for users to be able to query the stored data. This is not a simple task and a major obstacle to our implementation. We were unable to use our prepared SQL queries from the initial analysis because they were greatly simplified in comparison to the complexity of the Evita queries and did not provide the needed modularity of the Evita query language. There was a need to dynamically construct the SQL queries from the Evita query language on every new request. It was necessary to create a universal translation layer that supports all requirements of the Evita query language, yet it stays performant and behaves correctly even in corner-case situations. We embraced the way of modularity imposed on us by Evita and created a structure, which rather closely copies the Evita query language, allowing us to keep its expansive modulation.

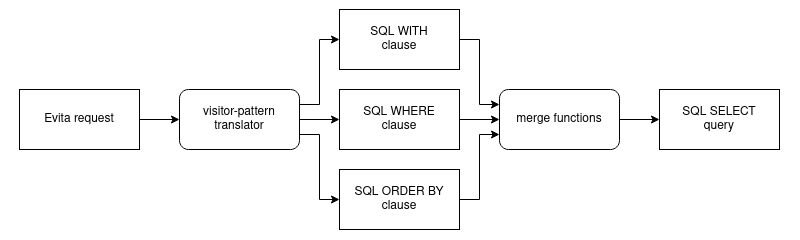

Evita request translation process

Evita request translation processTo finish this process, the translated SQL clauses are merged into the final SELECT command templates. Such a query is then executed against PostgreSQL via standard JDBC API which returns the entities in the binary form that gets deserialized using the Kryo library and sent to the client.

While this structure is unusual at first glance, it has its distinct advantages. The main advantage is that it allows for dynamic building of the SQL queries no matter what the input Evita request is. It is also relatively easily extensible with new translators when new constraints are added to the Evita query language. Another advantage helpful for testing and implementation is the ability to test each block individually regardless of other constraints to make sure that the solution works correctly on these atomic building blocks, eliminating the errors at the lowest level.

We fully acknowledge that this approach is slower than formerly prepared queries, and as such, we would not recommend its usage if it were possible to plan the SQL queries beforehand, an unfortunate impossibility for our use-case.

Paging

As part of the optimizations, we tried to reduce the possibility of repeating the entire query in case it fails to return data on a page other than the first. In this approach, we aimed at replacing the clauses used above by directly utilizing the number of returned records in the filtering conditions of the query and selecting the first page with zero offset in case the query returned nothing with the requested constraints. We achieved this result by writing an SQL function to calculate the appropriate offset based on the number of the found records that match the filtering conditions without any restrictions on pagination.

After running these queries over the test dataset of 100,000 entities, we measured their execution time: 500ms for the first approach and 650ms for the second new one. As these numbers suggest, some difficulties occurred, which made the optimized variant significantly slower and inappropriate for our use-case, than if we used the unoptimized one. For instance, in the tests focusing on paging with random page numbers or offsets, i.e., where this logic would be used, the performance gain was very noticeable (100% faster on average). However, in most other cases, where a page contained some data on the first try, it was rather damaging. In these cases, there was a noticeable decrease in the execution speed in the range of 30 to 50 percent. Based on this information, we concluded that in most cases, using the window function to solve paging is significantly more expensive for the DB. After evaluating these results, we decided to return to the original version of paging.

Querying entities in detail

It is no surprise that we encountered some difficulties while implementing different querying strategies. Each query strategy (query by attributes, hierarchy, facets, and prices) has unique requirements for the SQL conditions and context. Hence the detailed explanation of each strategy is provided below.

Querying by attributes

To query the entities by attributes, an attribute with the requested name and locale has to be found for each entity and its value has to be compared to the user-defined value. The attribute value can be either a single item or an array of items in case of certain filter constraints. If such comparison passes, the entity can be returned to the user as satisfactory. If the entities are queried by attributes of references, first references with those attributes have to be found and after that, the entities owning such references are returned.

Initially, we used subqueries inside the WHERE clause of the SELECT query for each compared attribute to find and compare its value:

Thanks to this, we were able to dynamically connect multiple constraints to construct complex queries.

Querying the whole table of attributes for each entity over and over again was not ideal. Therefore, we needed some way to query more optimally but with the great ability to construct any combination of constraints inside the WHERE part of the query to be able to combine attribute constraints with hierarchical constraints and more. As is has been mentioned above, we introduced the inversion of lookup for the first time. It consists of finding all attributes with satisfactory values in advance using CTE and WITH clause,

and then comparing if a particular entity resides in such a list in the WHERE part.

Using this method of visiting the attributes table only once for each attribute constraint in the Evita query proved to be much more performant. This brought approximately a 100% performance boost. In addition, we were able to embrace PostgreSQL index-only scans, which do not use secondary table lookups, to get the target values and achieve even better results.

Besides the whole logic of finding the actual attributes, there were also difficulties with different data types of attribute values. Evita supports a large variety of data types that can be used for attribute values. We could list, for example, integers, strings, ranges, booleans, or date times. In PostgreSQL, each column can only have one specific assigned data type which leads to an obvious mismatch. We could use the string data type and serialize every original data type to some string value which would enable us to have a single column for all attribute values. Unfortunately, this approach would lead to the loss of possible optimizations for individual data types on the PostgreSQL side, the most important of which are DB indexes. This choice would negatively affect the whole performance.

We decided to solve this issue by utilizing several columns for values, each with a different data type. Each attribute value is correctly assigned in a specific column during the serialization with the correct data type and other columns are left empty. When querying that particular attribute, the appropriate schema of the attribute is found, and depending on the data type in that schema, the correct column is selected for the search.

Indexes on attributes

We experimented with different types and configurations of DB indexes for attribute values. Our overarching goal was to speed up the queries as much as possible. First, we tried to dynamically create separate DB indexes for each attribute schema. This means that for the attributes with the same name, there was a single DB index. Our idea was to decrease the size of the attribute DB indexes to the necessary minimum because each entity collection usually has hundreds of thousands of attributes and when querying by attributes, each attribute constraint always specifies a name so we only search through attributes with that name. The unfortunate side effect of this approach is a disproportionate number of indexes, for the Senesi dataset, it led to around 12k DB indexes just for the attributes alone. This had a significant effect on slowing down the insertion of data as there were a lot of indexes to update. In comparison to a single DB index for all attributes (which included the attribute names), we detected no gain in querying entities by attributes. These dynamic indexes sometimes performed even worse (approximately by a few percent) than the single index. Therefore, we reverted to the single DB index for all attributes and focused on optimizing this approach.

We think that in the case of a single DB index with the included attribute names, PostgreSQL could more easily filter out the unwanted attribute values using the indexed names as opposed to having to search for the correct DB index by attribute name in PostgreSQL’s own tables. Due to time constraints, we did not have resources to prove or disprove this hypothesis.

Afterwards, we tried to experiment further with the shared DB index. We created separate indexes for each column containing a value joined with attribute names,

as well as a single DB index combining the name and all value columns:

Querying by hierarchy

This was one of the most problematic parts for us since we had to make a number of changes during the implementation not only to get everything working properly, but later on, we had to completely change our approach to processing the hierarchy.

Our next task was to identify the changes needed to allow for search of products only linked to the hierarchy, and not a part of the hierarchy itself. We solved this by simple wrapping previously mentioned subqueries with reference to hierarchical entity lookup.

Introduction of PMPTT into the hierarchy

The PMPTT library was a great help as it had already implemented all needed data structures. Since we also needed to support the indirect hierarchical querying through referenced hierarchy items, we introduced some changes. In the default state, each entity can have multiple references to other hierarchical entities, bringing even non-hierarchical entities into a particular hierarchy. Instead of storing all metadata, such as bounds and levels, directly with each item as columns, we opted for storing all metadata in a JSON column. This seemed a simpler and quicker approach at the time than using a separate table. Each entity had its own JSON object with records of the hierarchical placement of itself (in the case of a hierarchical entity) and referenced entities categorized by entity type and primary key.

This structure enabled us relatively easy access to all placements of queried entities without any joins and subqueries.

This approach proved to be much more performant than recursion, making this version at least comparable to other Evita Implementations. Therefore, we entirely dropped the recursion.

Later in the optimization phase, when we revisited hierarchy queries after further performance testing we found that no DB index could be effectively used to further speed up querying in the JSON objects mentioned above. Further testing and re-read of the PostgreSQL documentation led to an unfortunate discovery for us. PostgreSQL does not store statistics about the JSON columns.Therefore, it cannot properly and effectively query the complex JSON objects when read performance is the most important aspect. Due to this fact, we tried a more traditional approach with an additional table containing all hierarchical placements (with the same content as in previously used JSON objects) in conjunction with the columns containing hierarchical placement of itself directly (in case of a hierarchical entity) to minimize the need for joins and subqueries to the new table. In this new structure, we were able to create proper DB indexes on both bounds in the entities table as well as in the new table. Hierarchical entities could be queried directly using the new columns without any need for subquery or join. Entities with referenced hierarchical entities needed a simple subquery to the new table to lookup metadata of the required placement, which was also further optimized using CTE. This approach, which we initially rejected as it seemed to be a more difficult and less performant variant, turned out to be a surprising opposite as PostgreSQL could properly utilize indexes with high performance. Even the implementation was simpler because we did not have to use the long PostgreSQL operators for retrieving specific placement metadata from the JSON objects.

Querying by facets

To significantly speed up facet querying, a CTE is created for each such SQL condition to search entities once,

and then compare found IDs against the queried entities similarly to how attributes are queried.

Querying by price

Initially, we stored these prices in a range but that turned out to be suboptimal as we always needed two values. As a result, min and sum functions had to be computed twice for the NONE and SUM prices. Later, we replaced the ranges with arrays, because it allowed us to store only single price as well as multiple prices in a single structure.

Finally, such prices are joined to the queried entities exposing an array of selling prices by which the entities can be further filtered or ordered.

The array of selling prices of a single entity can then be used, for example, in the main entity query as follows:

or can be used to order in this way:

Ordering entities in detail

Ordering by prices is a trivial task after the selling prices are computed. We just take the computed array of selling prices and order the entities by the first price in the array.

Computing additional results

As it has been mentioned in the theory above, additional results are very complex and very individual. This complexity prevents the use of abstraction. Instead, we describe difficulties with each individual additional result as these were the most difficult not only to implement, but also to optimize. This also means that each additional result is computed separately.

However, one concept is similar enough for all additional results that it could be isolated and consequently abstracted. The concept of temporary tables to store the intermediate results of entities satisfying the baseline part of the Evita query. The idea is that all additional results use the entities satisfying the baseline part to compute the additional results with the help of the user filter part. Since the baseline part cannot be changed during query execution, we can cache such results as they will not change. The user filter, however, can change and is changed frequently during most of the computation of the additional results. This enables us to cache the pre-queried results without any need for querying the baseline part of the query multiple times, which would be quite expensive. We also reuse these intermediate results for fetching the entities, thus saving computational time further.

Facet statistics

First of all, it is necessary to find all relevant facets with a count of entities with such a facet for all entities satisfying the baseline.

These facets with their counts are then mapped to their groups. In case there are no relevant facets, we abort the computation altogether. For the negated groups of facets, the count of entities connected to these facets needs to be subtracted from the fetched counts. If we wanted only the facet counts, we could stop right here and simply map results from the above query to the additional results object because we already have all the necessary counts.

However, for the full facet statistics, a few additional steps must be involved. First, the user-selected facets need to be translated into the SQL conditions that can query through joined JSON structured facets.

This allows us to find the entities containing the selected facets between those which are returned by baseline. Afterwards, the whole SQL condition is used to compute the number of the entities that satisfy the whole canonical query.

After this preparation, we need to go through every relevant facet and calculate the entity count difference against the base count. It may seem like a simple task but unfortunately, it involves creating the new SQL conditions for every facet based on the SQL condition of the selected facets. Each facet needs to be assigned to the correct facet group which may reside in a group of already created SQL conditions. Therefore, the whole SQL condition has to be reconstructed. In addition, the relevant condition has to be executed against the baseline entities several times with a minor change each iteration. Finally, this count is subtracted from the base count and we receive the difference of possibly selected facets.

As it is obvious from the previous paragraph, this computational process is rather demanding. Especially when there are a lot of facets. The amount of individual calls to PostgreSQL is enormous and very expensive. We were thinking about moving this computation logic to the PostgreSQL functions and procedures, but there would be other complications, e.g., with passing the query data to these functions and creating efficient logic in PL/SQL. Therefore, it was necessary to implement caching and other optimizations. We use caching of entities satisfying the baseline, as once computed, we can reuse it numerous times for computing the counts of possible selected additional facets. If we did not use caching, we would have to query the whole DB for every such facet and that would be exceedingly slow.

The aforementioned caching is achieved by creating two additional tables, a temporary session-specific aggregation table and a global MV holding JSON aggregate of all entity facets from the reference table. A temporary table is created at the start of the Evita query processing with joined MV and is terminated at the end of the SQL session. This aggregate table contains one record for each entity that satisfies the baseline requirements. The JSON aggregate contains all facets for said entity categorized by referenced entity type. This JSON is used to filter the baseline entities by the selected facet SQL conditions.

It may occur to someone why we do not use the MVs for caching. The reason is that there are a few drawbacks to such usage. A table can be set as temporary, which means that DB deletes it by itself when it is no longer needed, the same cannot be done for MV. A table can be created with JDBC parameters, MV cannot. In addition, because each temporary table is tightly coupled with Evita requests, we do not need to refresh such tables. Therefore, the main advantage of MVs would not be used.

Hierarchy statistics

Hierarchy statistics displays a tree of hierarchy entities with counts of entities referencing them. Furthermore, the hierarchical entities without any associated entities (usually products) should not be displayed and this is true even for the associated entities filtered out by the current query. Again, we use the created temporary table as a starting point for relevant entities.

This is done by selecting this CTE and joining a sum of individual cardinalities of individual hierarchical entities computed in the previous step to each hierarchical entity. The sums of cardinalities are computed using PMPTT bounds by finding all cardinalities of the child hierarchical entities to the currently searched one.

Finally, these hierarchical entities with zero cardinalities are removed and all remaining entities are ordered according to the left bound of the PMPTT to form the final tree.

Parents

We then adjusted our methodology to make better use of the information contained in PMPTT bounds representing hierarchical placement in target collection, which enabled us to recursively find all parents of each entity without any need for real SQL recursion. Thanks to the PMPTT structure, we were able to find parent entities in linear time by comparing left and right bounds against the original hierarchy entities.

Histograms

During the implementation of histograms, it was necessary to use a similar system as for statistics, namely using the temporary aggregation table.

Attribute histogram

Price histograms

When computing price histograms, we use the logic of computing histograms on attributes that we have already discussed. We have added new information to the temporary tables, namely the information about the lowest selling price of each entity, computed in the same way as when querying for prices. The corresponding histogram is again computed based on this temporary aggregation table.

Appendix A: PostgreSQL selection rationale

This document contains a rationale that was created and written before the prototype implementation started. It's the output of the initial research phase where the team selected the particular relational database for prototype implementation. Some statements in this appendix might be inaccurate because they reflect the knowledge available at the very beginning of the project that evolved in time as the team learned the subtleties of the domain and the datasets.

Introduction

This work is intended as complementary research for evitaDB, mainly to answer one simple question. Is evitaDB better than traditional relational databases in its function? And if so, can we ascertain by how much? To answer, we prepared this document. You will find here contemplation on which relational Db should be chosen for our testing, reasons why we choose as we did, a model of our data representation that shows the inner structure of our DB and finally testing queries that show times measured, all hopefully helping to show a clear comparison to evitaDB.

Database platform selection

To present a better comparison to evitaDB, there were certain requirements that we had to meet in our Database selection.

Those requirements are:

- free to use

- well documented

- well known among developers

- fast

- HW/OS support, usability of Docker container

As such, we identified 2 main candidates to compare and choose from, MySQL and PostgreSQL.

Our main criteria are shown in a table below.

| Parameter[sources] | MySQL | PostgreSQL |

|---|---|---|

| DB is known for[1,3] | most popular (even with some concern with slower development speed since Oracle acquisition) | most advanced open-source relational database |

| Type of DB[1,2,3,4] | purely relational database | object-relational database |

| Preferred data volume[3] | small | large |

| Compliance to SQL standards[1,3,4] | not a fully SQL-compliant | supporting at least 160 out of 179 features required for full SQL:2016 Core conformance |

| Performance[3,4] | performance-optimization options are very limited. Without full SQL compliance, writing efficient and well-performing SQL queries can be a challenge. Tablespaces are only supported in InnoDB and cannot accommodate table partitions. Simple queries to hit tables can be made to complete faster by creating B-TREE Indexes | Highly suitable database for any kind of workload. Possible to write efficient queries and pl/pgsql programs. Several configuration options for allocating memory to a database and queries, and partitioned tables can be placed across multiple tablespaces to balance disk I/O |

| Indexes[1,2,4] | B-Trees | Bitmap, B-Trees, full-text, partial and expression indexes |

| Open-source stack[1,4] | LAMP[14] | LAPP |

| Partitioning[1,3] | supports declarative table partitioning. Partition types are RANGE, LIST, HASH, KEY, and COLUMNS (RANGE and LIST). From MySQL version 8.0, table partitioning is only possible with InnoDB and NDB storage engines | supports declarative partitioning and partitioning by inheritance. Partitioning types supported are RANGE, LIST, and HASH |

| Replication[1,2,3] | Primary-replica and Primary-to-multiple-replicas replication - asynchronous only(replicas can perform database writes). Supports NDB cluster | primary-replica and primary-to-multiple-replicas, including cascading replication. Utilization of streaming WAL(Write Ahead Log). Asynchronous by default, synchronous on demand. Support for logical replication. Tends to be faster than MySQL |

| Views[1,3] | Materialized views not supported. Views created with simple SQLs can be updated, while views created with complex SQLs cannot | supports Materialized Views, which can be REFRESHED, and indexes as well as views created with simple SQLs can be updated, the views created with complex SQLs cannot be updated. But there is a work-around to update complex views using RULES |

| Triggers[3] | AFTER and BEFORE events for INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE statements. Cannot execute dynamic SQL statements or stored procedures | AFTER, BEFORE, and INSTEAD OF triggers for INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE events. Can execute complex SQL as function. Can execute functions dynamically. If you need to execute a complex SQL when the trigger gets invoked, you can do this using functions. Yes, the triggers in PostgreSQL can also execute functions dynamically. |

| Stored procedures[3] | only supports standard SQL syntaxes | supports very advanced procedures. Functions with a RETURN VOID clause support. It has for various languages that are not supported by MySQL, such as Ruby, Perl (PlPerl), Python (PlPython), TCL, Pl/PgSQL, SQL, and JavaScript |

| JSON support[3,4] | from Version 5.7. JSON-specific functions limited. No full-text indexing | from version 9.2. Advanced. Full-Text Indexing (known as GIN Indexing) |

| Security[3] | via ROLES and PRIVILEGE. Supports SL-based connections over the network and provides security based on SE-Linux modules. | via ROLES and PRIVILEGES using GRANT commands. Connection authentication is done via a pg_hba.conf authentication file. Supports SSL-based connections and can also be integrated with external authentication systems, including LDAP, Kerberos, and PAM |

| Features that other lacks[1,2,3,4] | pluggable storage engines | Materialized view. Full outer joins, intersect, except. Partial Indexes, Bitmap Indexes, and Expression Indexes. CHECK constraint. ARRAYs, NETWORK types, and Geometric data types (including advanced spatial data functions)[3]. LIMIT & IN/ALL/ANY/SOME subquery[3]. NESTED window functions are supported[3] |

| Supported HW/OS | Windows, MacOS, Linux (Ubuntu, Debian, Generic, SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, Red Hat Enterprises, Oracle), Oracle Solaris, Fedora, FreeBSD, Open Source Build[12] | MacOS, Solaris, Windows, BSD (FreeBSD, OpenBSD), Linux (Red Hat family Linux including CentOS/Fedora/Scientific/Oracle variants, Debian GNU/Linux and derivatives, Ubuntu Linux and derivatives, SuSE and OpenSuSE, other Linux operating systems)[13] |

| Docker containerization[17] | Yes[15] | Yes[16] |

After evaluating all factors in the table and even those that can not be easily quantified, we decided to proceed with PostgreSQL, our reasoning is as follows. Both Database engines are free-to-use(as of this writing), well documented and known among developers.

OS support is also fairly broad for both, and while PostgreSQL support is broader, MySQL is supported on all main platforms that we can expect to run it on. As for the containerization, both are fully supported without issues.

Our main deciding factor is then speed, sadly that is not as easily concluded. There are numerous benchmarks for one or another, with no clear winner. It can be broadly said, that MySQL is faster on small Databases with relatively simple queries, while PostgreSQL excels on BigData and complex queries.

As can be seen from the table above, PostgreSQL also provides more options, not only for usage but also for optimization, where MySQL is quite lacking. As evitaDB is also expected to perform complex queries, PostgreSQL has a clear advantage.

Finally we need to consider the future, and here PostgreSQL once again takes the lead. MySQL development has been slowed since acquisition by Oracle, PostgreSQL on the other is well known as the most advanced relational DB.

Which unique features of PostgreSQL will be taken advantage of then? For start, we plan to utilize:

- better performance for complex queries[2,4]

- better queries optimization possibilities because of adherence to SQL standard[1,2,3]

- supports inheritance among tables

- Range type[11]

What is its potential for the future (ie. solved cluster scaling, fulltext integration ...)

- PostgreSQL doesn’t support scaling by itself, but there is a lot of solutions to achieve that goal[8]

- Pgpool-II provides: connection pooling, replication, load balance, parallel queries, limiting exceeding connections[9]

- built-in fulltext search with several built-in language dictionaries and support for custom dictionaries[10]

Model representation

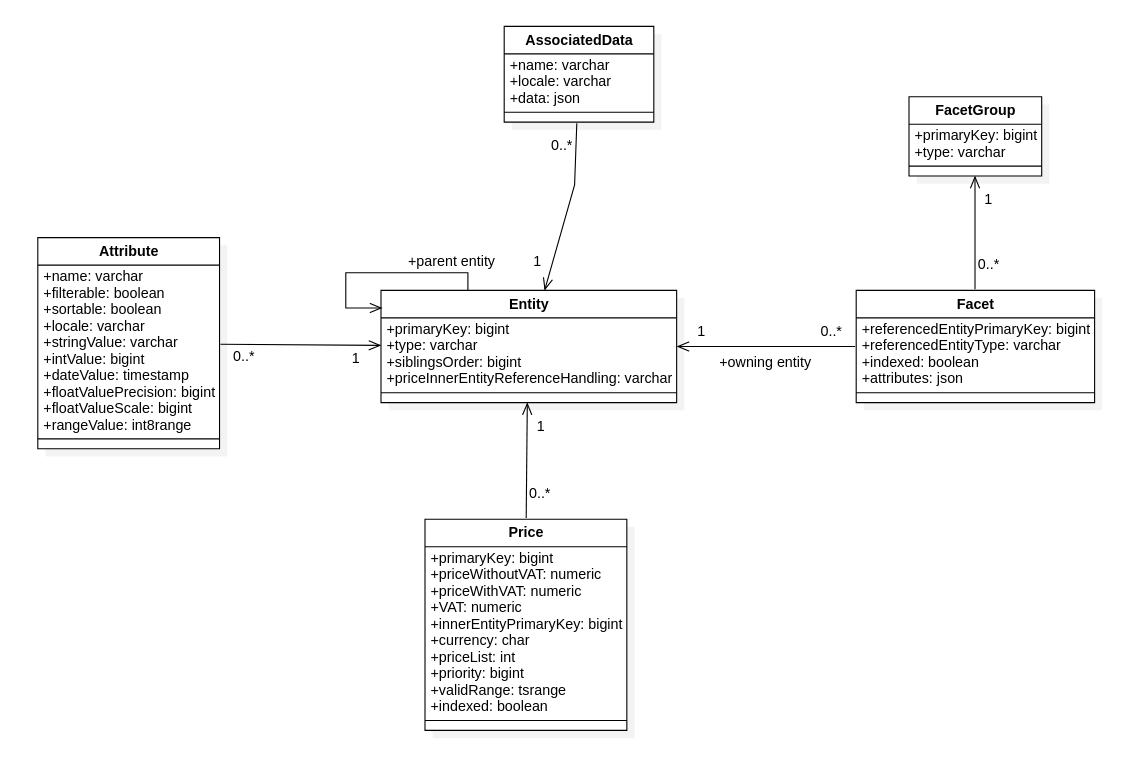

Evita model

Evita modelOur model is represented by tables in the underlying RDBMS, where one table stands for one logical part of it, such as an entity or an attribute. Big data are stored in one column as json data type if searching isn’t required.

Consistency tasks will be handled by database server, in a schema-full approach we will validate against schema specified by the user of our implementation. If necessary, additional checks may be implemented.

Model evolution

Model is designed as schemaless by default. Users of our implementation can index whatever entity they want with whatever attributes, facets, prices, etc. In this case only most needed validation checks for consistency in the underlying system are being run and structure consistency must be ensured by the user of our implementation.

If a user chooses to use the schemaful approach, then schema in DDL must be passed to DB before entity indexing. While indexing new entities the schema is used to validate entity structure on top of most needed validation checks in the underlying system. Stored indexed data will be then considered as valid and will not be validated when querying.

The structure schema for validating will be stored in separate RDBMS tables and will be used by the indexing engine of our implementation.

Query modeling

During analytic phase following queries were built to test that the designed model can deliver all data we need from evitaDB in reasonable times.

Testing

- 4 cores from Intel Xeon Gold 6146

- 6 GB RAM of DDR-4, 2666 Mhz

- 40 GB of 2 TB SSD with SAS interface, read speed 2100 MB/s write speed 1800 MB/s

The testing queries were run against generated dataset of these row counts:

| Table | Count |

|---|---|

| Entity | 100000 (35% were products) |

| Attribute | 3000000 |

| Facet | 1200000 |

| Price | 300000 |

| Assoc. data | 3000000 |

| Required output | Time [ms] |

|---|---|

| Select all products that are in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) | 246 |

| Select all products that have 3 attributes equal to some value | 176 |

| Select all products that have validity within range of two dates | 177 |

| Select all products with most prioritized price (of certain price lists - for example a, b, c) >= X and <= Y | 115 |

| Select all products that have CZ localization (at least single CZ localized text) | 204 |

| Select all products that are in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) and select its most prioritized price (of certain price lists - for example a, b, c) >= X and <= Y | 279 |

| Select all products that are in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) and their validity is within range of two dates | 389 |

| Select all products that are in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) with most prioritized price (of certain price lists - for example a, b, c) >= X and <= Y and their validity is within range of two dates | 485 |

| Select all products that are in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) and have 3 attributes equal to some value and their validity is within range of two dates with most prioritized price (of certain price lists - for example a, b, c) >= X and <= Y and have at least one CZ localization text | 1004 |

| Select all products with most prioritized price ordered by price ascending (of certain price lists - for example a, b, c) >= X and <= Y | 110 |

| Select all products by localized name or selected attribute ascending | 135 |

| Select categories and render complete tree of them | 443 |

| Select subtree from specific category | 38 |

| Select all facets of product in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) | 394 |

| Select all facets of product in a certain hierarchy (ie. category A or its subcategories) and compute counts of products that posses such facet | 405 |

Conclusion

In conclusion, we had good reasons to work with PostgreSQL, which we explained in the section Database platform selection. In the next section, we introduced a model that meets requirements and also enhances desired functionality.

In current stages, we explore how we may enhance our performance by means of optimization on DB and on our queries.

Resources

- https://www.upguard.com/blog/postgresql-vs-mysql

- https://www.codeconquest.com/versus/mysql-vs-postgres/

- https://www.enterprisedb.com/blog/postgresql-vs-mysql-360-degree-comparison-syntax-performance-scalability-and-features#performance

- https://www.xplenty.com/blog/postgresql-vs-mysql-which-one-is-better-for-your-use-case/#howiscodingdifferent

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/sqlite-vs-mysql-vs-postgresql-a-comparison-of-relational-database-management-systems

- https://www.slant.co/versus/616/4216/~postgresql_vs_mysql

- https://eng.uber.com/postgres-to-mysql-migration/

- https://wiki.postgresql.org/wiki/Pgpool-II

- https://www.highgo.ca/2019/08/08/horizontal-scalability-with-sharding-in-postgresql-where-it-is-going-part-1-of-3/

- https://www.postgresql.org/docs/9.5/textsearch-intro.html#TEXTSEARCH-INTRO-CONFIGURATIONS

- https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/rangetypes.html

- https://dev.mysql.com/downloads/mysql/

- https://www.postgresql.org/download/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LAMP_%28software_bundle%29

- https://hub.docker.com/_/mysql

- https://hub.docker.com/_/postgre

- https://rancher.com/containers-and-postgresql-vs-mysql-vs-mariadb